Power’s Ratio

What is Power’s Ratio?

Generally speaking, since 1979 Power’s ratio measurement has been utilized by radiologists to assess for atlanto-occipital dissociation (skull to first vertebrae instability or dislocation); and described more specifically, horizontal, anterior atlanto-occipital instability.

To understand what an abnormal power ratio is, it is essential first to know the anatomy of the atlanto-occipital joint, which is related to it.

WHAT IS THE ATLANTO-OCCIPTAL JOINT?

It is formed between the first vertebrae of your neck (the atlas) and the base of your skull (the occiput). The following ligaments stabilize this joint:

-

-

- Cruciform ligament

- Alar ligament

- Anterior atlanto-occipital membrane

- Posterior atlanto-occipital membrane

-

WHAT SHOULD I KNOW ABOUT THE POWER’S RATIO?

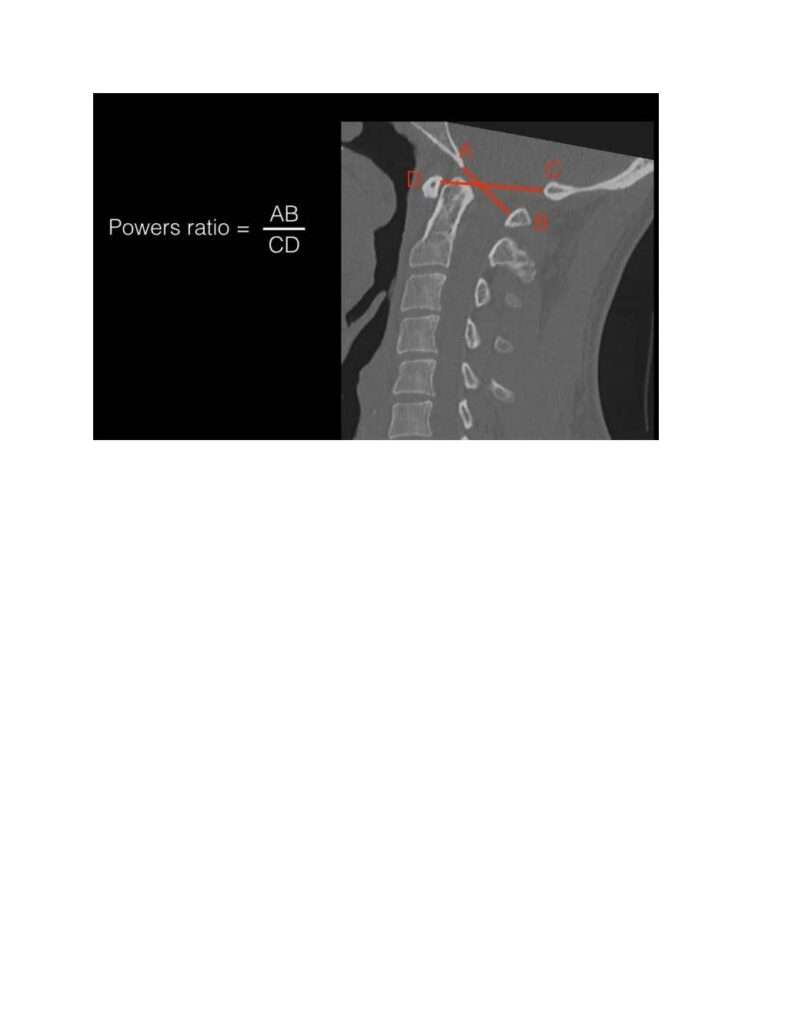

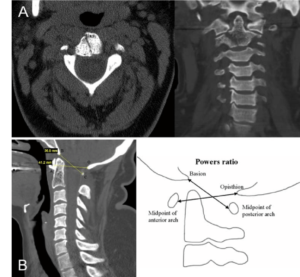

Power ratio has been used in the evaluation of atlanto-occipital dislocation. It is defined as the ratio of the distance between basion (A) and posterior spinolaminar line (B) of the atlas to the distance between opisthion (C) and anterior arch of the atlas (D). The formula can be represented as below:

Power ratio = AB / CD

Normal ratio: On X-ray, the typical ratio is less than 1. However, on a CT scan, it is less than 0.9.

Abnormal ratio: Anything that comes out greater than one is considered abnormal.

Significance: This ratio is increased in the cases of anterior atlantooccipital joint dislocation. However, it has no clinical relevance, and we can only use this measurement to a small extent when it comes to the posterior or inferior displacement of the joint.

WHAT SYMPTOMS CAN BE EXPERIENCED IN THIS?

Atlantocccipital joint disruption, which affects the power ratio, can present with a wide range of symptoms, which can be due to either traction/compression of that part of the spinal cord which passes through the joint, brain stroke due to artery damage, or cranial nerve damage. The latter is responsible for the sensation and movement of all parts of our head, like the eyeball, mouth, tongue, etc.

Compression of cord: Loss of sensation or paralysis on one or both sides and incontinence due to loss of the anal or bladder sphincter tone.

Cranial nerve damage: Difficulty swallowing, difficulty speaking, paralysis of the tongue, stiffness of neck movement.

Ischemic stroke: Numerous signs depending upon the severity .

It should also be noted that injury to the brain stem could also result in respiratory arrest and death.

WHAT CAN CAUSE AN ABNORMAL POWER RATIO?

Anything that disturbs the atlantooccpital joint can cause an abnormal power ratio. The following are the possible causes listed in order of frequency.

-

-

- Trauma that includes hyper-extension, hyper-flexion, or rotational injuries of the neck. One example is whiplash-like injuries.

- Rheumatoid arthritis affects the atlantooccipital joint.

- Down syndrome results in the laxity of ligaments.

- Congenital cervical vertebral fusion syndromes

-

How do Radiologists measure Power’s Ratio?

The Powers ratio is a measurement of the relationship of the foramen magnum to the atlas, used in the diagnosis of atlanto-occipital dissociation injuries.

The ratio, AB/CD, is measured as the ratio of the distance in the median (midsagittal) plane between the:

Normal values are <1 on plain radiographs 1 and <0.9 on CT 2. If this ratio is >1, then the anterior atlanto-occipital dissociation should be suspected 2. However, Powers ratio is not useful in diagnosing posterior dissociation and vertical distraction injuries 2. Reference

Image: Diagram illustrating the landmarks used to determine the Powers ratio, including the midpoint of anterior arch (A), the opisthion (O), the basion (B), midpoint of posterior arch (C). A BC/AO ratio of > 1.0 indicates atlanto-occipital dislocation.

Diagnostic Imaging

The sensitivity of the Powers ratio in the detection of anterior atlanto-occipital dissociation on lateral cervical spine radiographs (XRays) has been found to be between 33% and 60%. Reference

Measurements using CT images were more reliable with regard to intra- and inter-observer agreement, making CT superior to XRay. Reference If CT is not accessible, patients can try to find a CBCT at an upper cervical chiropractor clinic or imaging clinic.

If XRay or CBCT/CT shows an abnormal Power’s Ratio measurement, the treating physician should order a MRI to rule out spinal cord injury. If none is present on supine MRI, then a dynamic uMRI flexion-extension would be helpful to investigate atlanto-occipital instability in flexion and/or extension.

Read more information on dynamic imaging.

HOW SHOULD I GET THIS TREATED?

Treatment begins as soon as the injury is suspected. In-line stabilization of the neck is the first step to make sure there is no further injury to the area.

In severe cases, surgical treatment is necessary. These include halo immobilization or occipito-cervical fixation and fusion. The latter is when the back of your head and neck are held together to keep them stable. The fixations can be done with screws too. These are used carefully to avoid damaging blood vessels, and you will be anesthetized to be pain-free..

HOW MUCH RESEARCH IS BEING CONDUCTED ON THIS ISSUE?

Because of the lack of clinical significance of the power ratio, little research has been conducted. Most of these are case studies, which are in third place when it comes to the level of evidence showing the value of the finding. Research that is in first place evidence-wise has been conducted, but these are several years older, although still relevant.

References:

- Tubbs RS, Hallock JD, Radcliff V, Naftel RP, Mortazavi M, Shoja MM, Loukas M, Cohen-Gadol AA. Ligaments of the craniocervical junction: a review. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2011 Jun 1;14(6):697-709.

- Powers B, Miller MD, Kramer RS, Martinez S, Gehweiler Jr JA. Traumatic anterior atlanto-occipital dislocation. Neurosurgery. 1979 Jan 1;4(1):12-7.

- Garrett M, Consiglieri G, Kakarla UK, Chang SW, Dickman CA. Occipitoatlantal dislocation. Neurosurgery. 2010 Mar 1;66(suppl_3):A48-55.

- Horn EM, Feiz-Erfan I, Lekovic GP, Dickman CA, Sonntag VK, Theodore N. Survivors of occipitoatlantal dislocation injuries: imaging and clinical correlates. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2007 Feb 1;6(2):113-20.

- Tubbs RS, Hallock JD, Radcliff V, Naftel RP, Mortazavi M, Shoja MM, Loukas M, Cohen-Gadol AA. Ligaments of the craniocervical junction: a review. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2011 Jun 1;14(6):697-709.

- Garrett M, Consiglieri G, Kakarla UK, Chang SW, Dickman CA. Occipitoatlantal dislocation. Neurosurgery. 2010 Mar 1;66(suppl_3):A48-55.

- Joaquim AF, Schroeder GD, Vaccaro AR. Traumatic atlanto-occipital dislocation—A comprehensive analysis of all case series found in the spinal trauma literature. International Journal of Spine Surgery. 2021 Aug 1;15(4):724-39.

- Formentin C, dos Santos LD, Maeda FL, Tedeschi H, Ghizoni E, Joaquim AF. Traumatic Atlanto-occipital Dislocation in Children Followed by Hydrocephalus–A Case Report and Literature Review. Arquivos Brasileiros de Neurocirurgia: Brazilian Neurosurgery. 2022 Sep 6.

- Garvayo M, Belouaer A, Barges-Coll J. Atlanto-occipital dislocation in a child: a challenging diagnosis. Illustrative case. Journal of Neurosurgery: Case Lessons. 2022 Mar 14;3(11).

Ref. Prof. AB May 2023